Daisy Supply Chain

Ever wonder where those flowers in the grocery come from and why, no matter what time of year, there are always roses available? Just in time for Mother's Day—the second busiest floral day behind Valentine's Day—we look inside the billion dollar flower industry and trace the well oiled supply chain that makes sure saying it with flowers is always an option.

A flower display at a Concord, NH grocery store at 4pm on Valentine's Day. How about some baby's breath? | Photo: Molly Donahue

Think about Valentine’s Day. Not the stuffed animals and chocolate and cards… zero in on those flowers. Roses. Probably red. Probably a dozen of them. But here’s a quandary that perhaps you haven’t really thought a lot about: Valentine’s Day is in February, right? Where the heck are roses coming from in the dead of winter?

Credit: Logan Shannon & Molly Donahue

The florist? Sure, maybe. If you’re anything like our team, you’ll probably head over to the grocery store first to see what they’ve got. If you’ve waited until 5pm on Valentine’s Day, the selection is probably going to be a little sparse.

But just stop and think about this for a second: those roses that you’re squabbling over in the grocery store aisles, how did those even get there?

Fresh-cut flowers are nature’s most ephemeral phenomenon. Poets have written whole collections using the blossom as a metaphor for the briefness of life. But they rarely write sonnets about how the humble flower affects a country's gross domestic product.

In this episode, we’re tracing the path a cut flower takes, step by step. We looked inside the $31 billion American floral industry to show you what it takes to ensure that nature’s shortest lived product will arrive to the grocery store or florist’s fridge and then make its way onto your kitchen table looking fresh as a daisy. And that means starting down south. South America south.

From Domestic Product to International Import

Today, roughly 80% of our imported flowers come from Ecuador and Colombia. But this wasn’t always the case. Most flowers sold in the U.S. used to be grown in the U.S. New Jersey had a handle on the rose market until it became more economical to move it to California where real estate wasn’t as valuable (yet). Colorado, with high plateaus, warm days, and cool nights was also a big producer. But in 1967 a graduate student in horticulture named David Cheever at Colorado State University asked a key question: Where’s the best place in the world to grow flowers?

Amy Stewart is the author of Flower Confidential and the woman we turned to for expertise on the flower industry. It turns out it places like Ecuador and Colombia, regions along the equator with high plains, cool nights, and low labor costs are the best places to grow flowers. Here’s a hint from Amy, “Roses happen to grow very well along the equator, they like warm days and cooler nights and the stems get very long.” Another advantage to places like Colombia: Bogota is a convenient 3 hour flight from Miami—which will make sense soon.

Business flocked down there in the 1970s. Colombia now exports more than a billion dollars worth of flowers each year, and most of that comes to the U.S. Other South American countries like Ecuador, Guatemala, and Costa Rica followed suit, but Colombia still has the biggest share.

This fundamentally changed the way we buy flowers here in the U.S. Before the 1970s, flowers weren’t really sold in supermarkets. The business in Colombia was just so successful that all the blossoms coming into the country needed outlets other than florists. And thus the supermarket/bodega bouquet was born! Which illustrates the point that flowers don’t just do really well in these regions, they also do really well for these regions, at least in terms of making money.

The South American Flower Machine

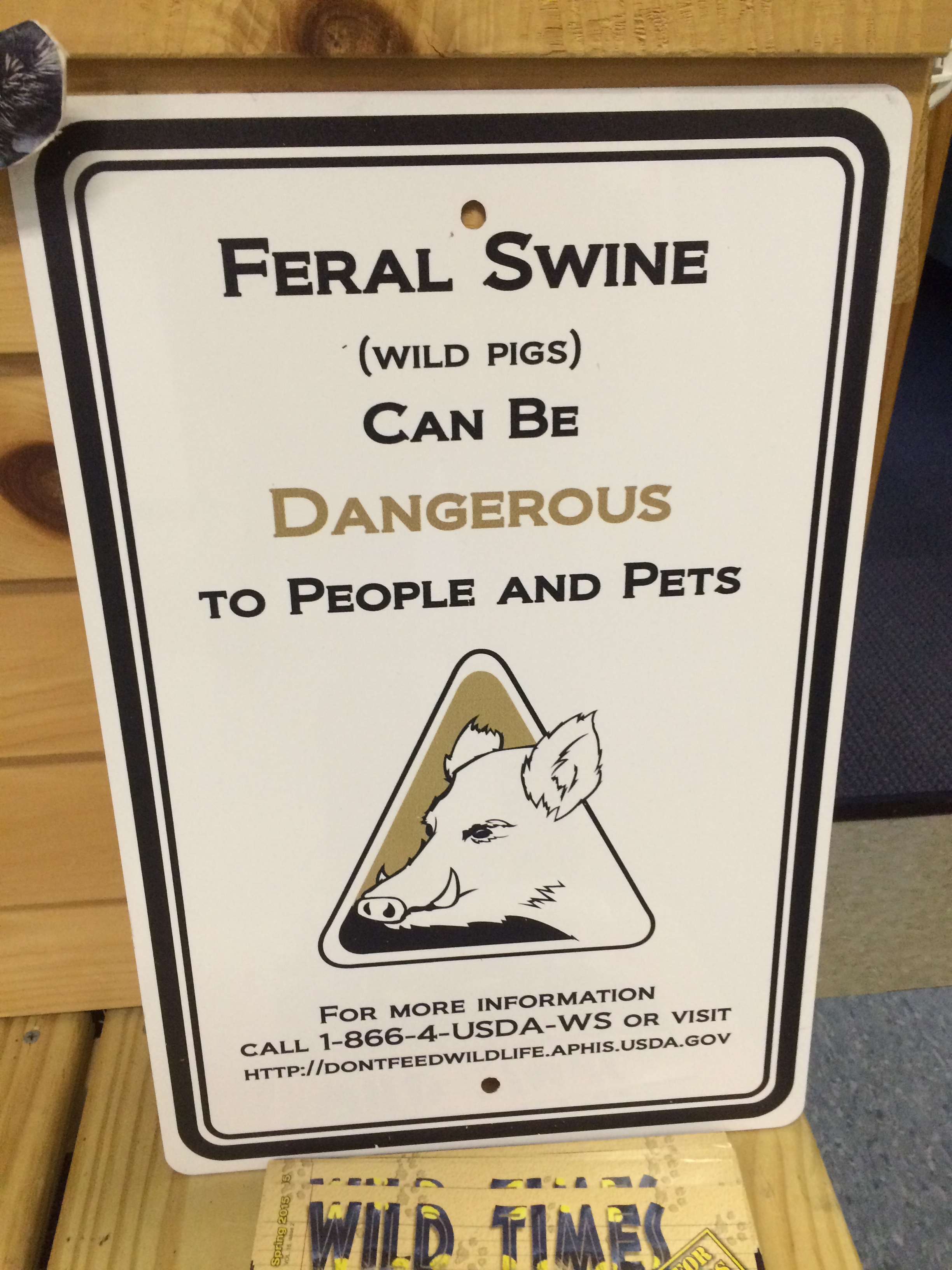

Carolina Loza Leon, is an Ecuadorian audio producer who went to check out the rose industry on our behalf. She visited several of the rose farms that blanket the region around Quito, Ecuador. She described the scene at one of the greenhouses near Tabacundo, Ecuador. There are some workers weeding, while another sprayed down the rows with some sort of chemical. According to Carolina, “There’s a guy zigzagging through rows and throwing pesticides, fumigating...He’s all covered but the rest are not covered, they’re wearing long sleeves and gloves and hats.”

Because flower don’t go through the same inspection process as produce entering the United States, the emphasis is on making sure there is nothing visually wrong with the product—no bugs, no fungus. So, there is a lot of spraying of these flowers and at least at this one greenhouse, not a lot of precautions for the workers. Carolina said about ten minutes after being exposed to the spray, her arms started itching, and some of the workers laughed when they saw her scratching.

In the 19th century, people literally said it with flowers. Floriography was a kind of code used by chaste lovers to express their deepest feelings. | Credit: Logan Shannon

This seems like a good time to point out that this story isn’t an exposé on labor practices and pesticide use in the flower growing industry. But from what we heard from Carolina, and from looking at what other reporters have found, it's fair to say it's a mixed bag: workers are exposed to some nasty stuff. Including some pesticides that are illegal to use here in the U.S. But it's also an industry that has bolstered the local economies of flower growing regions. 90,000 people are directly employed by the Colombian flower industry, while another 40,000 work for companies that support it.

Among the people Carolina spoke with was Jose Ivan Chorlango Sanchez. He goes by Don Ivan. He owns his own small flower farm in La Esperanza, north east of Quito. He explained the time table that goes into growing roses—some will need to be cut in a few weeks, other a month. While this might seem like a hassle, there’s a reason flowers rule this area.

In this region, prices and demand for produce is much lower. “Here, we’ve seen that there is no other business as good as this.” Don Ivan said. “Tomatoes, prices are low, demand is low. Same with potatoes...I’d need at least 5-6 hectares for potatoes to work.”

That 5-6 hectares comes out to about 12 acres, which isn’t much land by American standards, but if you’ve just got a little plot of land in the Ecuadorian Highlands, you can make a living with just a couple greenhouses, growing batches of a few thousand roses at a time.

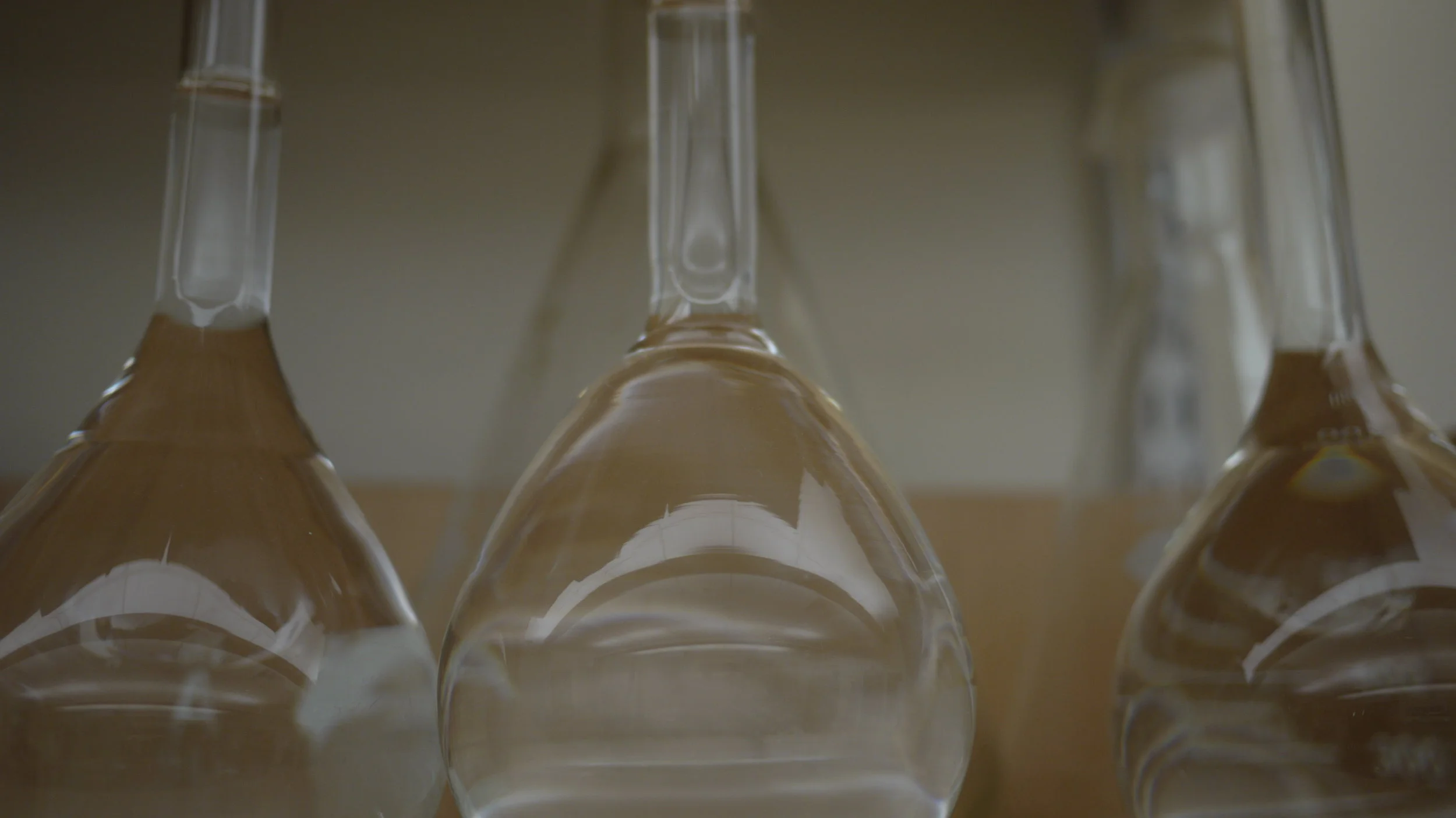

In Don Ivan’s greenhouses, he starts cutting at around 7:00 am for about two hours, then there’s weeding and cutting off buds so stock grows straight. Cut flowers are put into water to be “hydrated” then packed off to the processor, where they’ll be classified, cut down again, and stored in a cold room.

Don Ivan’s processor is the Asociación de Productores Agrícolas Pedro Moncayo. It’s a co-op, formed as a way for smaller farms to group together and sell their flowers to wholesalers. It’s an alternative for smaller farms, formed in response to poor conditions of bigger farms in the area.

“So, while a single rose might cost you a couple of bucks in the grocery store, most of that money isn’t going to the growers themselves. It’s going to the rest of the supply chain that gets that rose to you.”

Isabel Ramirez is the director of the Asociación, and she explained the cycle between two major floral holidays: Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day, two big booms for the flower industry that come just a couple months apart.

For small-scale growers trying to satisfy demands, it makes sense to have an Asociación like this handling your sales. Someone like Don Ivan can still be in the greenhouse cutting by 7:00 am, while Isabel’s sales team can come in early to handle sales calls on Moscow time.

Isabel explained that when her sales team comes in early in the morning they overlap for just a few hours with Russian buyers who are just about to head home for the day. Selling to folks in time zones in the U.S. is much easier. And all of this adds up to a setup that really works for smaller growers like Don Ivan, who says he gets about $0.33 per rose through the Asociación, more than he used to get through other processors.

So, while a single rose might cost you a couple of bucks in the grocery store, most of that money isn’t going to the growers themselves. It’s going to the rest of the supply chain that gets that rose to you.

“Alex Madrigal has a great line in his audio-documentary Containers that nothing ships by air except: ‘fresh flowers and fuck-ups.’”

Whether or not a flower is coming from an association or a big farm, flowers end up packed together and trundled off to a distributor, then stuffed onto a freighter plane or in the space left in cargo holds of passenger planes. These are usually some of the last flights to leave at night, to limit time spent idling on hot tarmac. This is actually a wild part of this process, since nothing else really gets shipped by air these days. Alex Madrigal has a great line in his audio-documentary Containers that nothing ships by air except: “fresh flowers and fuck-ups.”

After their luxurious airplane trip, flowers wind up—almost always—in beautiful, tropical, Miami. Why Miami?

Amy said, “Most of the flowers in the United States come through the Miami International Airport because they have a cold storage facility there that’s ready to receive flowers and food and it’ll get inspected and go on a truck. So maybe by Wednesday or Thursday it’s on a truck driving across the country to wherever you live and it might at that point make its way into a wholesale market or a distributor where it’s once again going to be in some kind of cold storage for a day or two or longer.”

The Regional Wholesale Market

Emily Herzig loads fresh flowers into her van at the Boston Flower Exchange on a cold winter day. | Photo: Molly Donahue

Let’s back up for a minute. It’s those wholesale markets that caught our interest and lucky for us there’s one right nearby: The Boston Flower Exchange (though it recently moved and has a new name: The New England Flower Exchange).

It’s basically the flowery version of a fish or meat market, complete with very local vendors hawking their wares. It’s catered to people who really care about their arrangements looking good, and who want to see what they’re getting before they buy it. Because getting a bunch of wilted flowers off the internet does not work for high-end florists and many local vendors.

Since you need someone in the industry to escort you in the Exchange we called up Emily Herzig. She owns the Emily Herzig Floral Studio up in Littleton, New Hampshire, and was nice enough to let us tag along with her.

While Emily was piling up her double decker cart at one of her vendors run by Chris Goodman, we learned one of the core tenants of coming to a place like the flower exchange: it’s about quality, not quantity.

Chris started working summers in his family’s flower shop in high school and 25 years later he’s racked up some surprisingly global connections. 80% of the flowers imported to the US come from South America, but that last 20% are coming from all over the world. There are certain trade routes that are much more popular (we get most of our flowers from South America, while Europe relies heavily on Africa) but this is definitely a global industry.

It has to be, because when a person is getting married, they don’t really care that lily of the valley are out of season. So their hardworking florist will haggle with their wholesaler and they’ll track down some lily of the valley from Japan...for a price of course. But a big chunk of the floral industry isn’t being run through wholesale markets anymore, and that’s because these days most people aren’t getting their flowers from the shop downtown. They’re either going to the supermarket or they’re going to the biggest store on earth: the internet.

From the Internet to Your Doorstep

We’re talking about FTD, internet flower juggernauts. To be fair, FTD has been around much longer than the internet; it was founded in 1910 as Florists’ Telegraph Delivery. And it’s not the only “Big Flora” business out there. There’s 1-800-Flowers, Teleflora, Pro-Flowers, every other flower related play on words you can imagine.

Most of these big companies work in similar way. Let’s say you live here, in the NHPR studios, in Concord, NH. But you want to send flowers to a friend in Austin, TX. In the FTD universe, you can go to your local florist and place an order with them. They transfer that order to a local florist in Austin, through an FTD network. Bing, bang, boom! Your florist gets a percentage, FTD gets a cut, and that local florist thousands of miles away gets a sale. That sort of transaction makes up a big part of the flower market—Teleflora claims to have 15,000 shops in its network alone.

After a boom in the market in the 1990s, the number of retail florist shops in the U.S. dropped—but the industry value continued to grow. Remember? $31 billion. And at the end of this long and wild supply chain—from a greenhouse in Ecuador, to an airport in Miami, to a wholesaler or market, then through a retailer to your doorstep—that’s still a lot of roses. Even when they’re going for a couple dollars a stem. So why roses?

Well, roses are available and in demand. And according to Amy the best selling flowers aren’t necessarily the best loved flowers—they’re just the ones we’re used to buying. “We used to just sort of roll with that and those were the flowers we wanted because those were the ones in the field, but we’ve gotten used to this more technologically advanced way to growing things where if you want a rose in February, you get a rose in February even though that’s kind of an absurd idea.”

So, if Valentine’s Day happened any other time of year, like summer, we might be giving bunches of dahlias, not roses. Genetically modified roses, at that, bred for size and color and lacking in any scent. (It’s true! Give those roses in the grocery store a whiff. A rose by any other name, would smell as sweet, but those sure don’t.) Which brings up another question: if people want huge, colorful flowers...why not just get silk ones?

“We’ve gotten used to this more technologically advanced way to growing things where if you want a rose in February, you get a rose in February even though that’s kind of an absurd idea.”

Here’s what Amy had to say, “We can all spot a fake and I think it’s not the point. The point is not to have a colorful blob, but the point is to bring some of the outdoors inside. You know, to have something of nature, but also something that’s kind of exotic.”

If this is all getting too big, too industrial, if there are too many voices trying to explain this system to you: don’t worry. Remember Emily, the floral designer from earlier? She’s your other option.

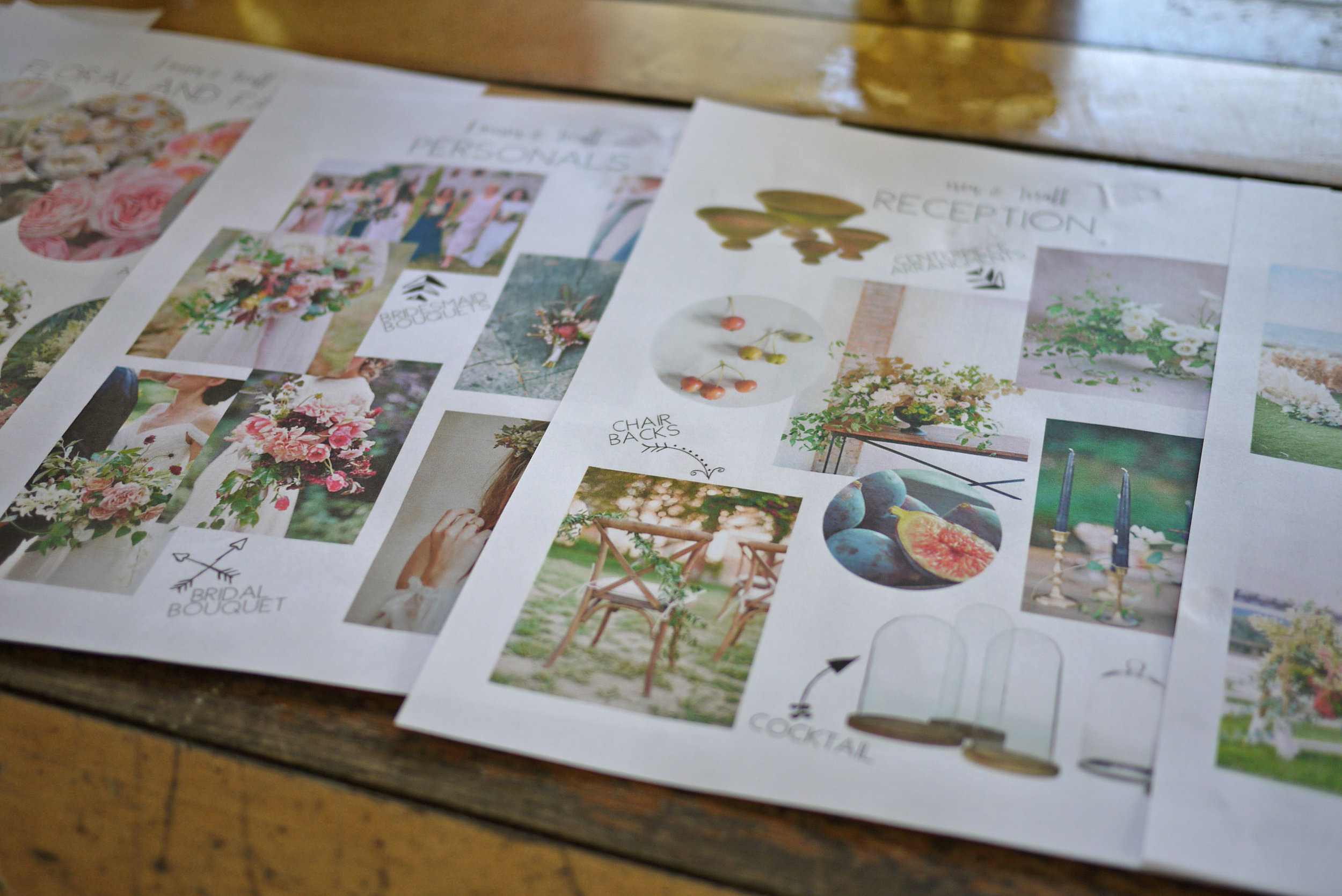

Farm to Vase

Producers Molly Donahue and Logan Shannon visited Emily Herzig’s studio in Littleton, NH where she was gearing up for that other boon for the floral industry: wedding season. Beginning in May, they’ll start doing more events, about 40 over the course of the summer, and that’s on top of the normal “say it with flowers” sorts of days, stuff like birthdays, special occasions, and of course, apologies. We caught her chatting with Emma Brumenschenkel, her assistant and all around right-hand woman.

If you’re uncomfortable with the whole flower supply chain thing, the other option is something Emily and Emma work with fairly often: local plants and flowers. The American Grown flowers movement is picking up steam, educating people about the potential profit in flower farms. In Emily’s case, she does try to work with more local flower growers, because it’s a popular option, but there’s a lot of practical reasons too:

“Floret Farms, which is actually in the Skagit Valley over in Washington, she’s a big leader of this movement where she’s doing a lot of education and training for people to grow flowers and realizing that it’s a really profitable farming opportunity that we have. There’s a need for it and it’s environmentally better to be sourcing things from within the United States...cutting down on that carbon footprint of things being shipped from all over the world.”

And Amy Stewart made a good point about this too, “When you buy local flowers, you’re not just supporting a local farmer growing flowers, you may well be supporting someone who’s also growing your food and trying to find a way to make that [aspect of their business] financially viable for them.”

This is all well and good, but there’s a reason New England isn’t the nation’s bread basket. We’re not exactly in a prime flower growing zone here, which makes sourcing locally a little tricky. Emily said she sometimes has challenges getting enough quantity, especially from local farms like Tarrnation Flower Farm that runs its own shop, and that means she has to find several sources for the same kind of flower. Or, if you’re really lucky, she might just go foraging for your event.

There’s a reason we pick up flowers from the supermarket, or put in a rush order for a bouquet when you’ve forgotten your friend’s birthday, and why silk flowers simply will not do. Emily’s assistant Emma put it like this, “You walk [into a special event] and there’s nothing and when we walk out of there and it’s like a completely different world. It’s definitely so important.” But, if you want to opt out of this wild and crazy industry, but you still want to give someone a little bit of the outdoors, maybe say no to giant bouquets wrapped in cellophane on Mother’s Day and Valentine’s Day, or at the very least forgo the roses. Mix it up a little!

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Molly Donahue and Sam Evans-Brown, with help from, Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Logan Shannon, and Jimmy Gutierrez.

Special thanks go to the Society of American Florists and their CEO Peter Moran. Also, thanks to Emily for bringing back the bonsai Sam bought then forgot on her cart - it’s doing well in its new home.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.